Framer

Does Legal Market Need Legal Engineers?

Preamble

Legal work is increasingly exposed to modern technology, making optimization and automation inevitable for the legal industry. While traditional legal tech teams of lawyers and tech experts can lead this change, legal engineers bring unique efficiency and effectiveness to the evolution of law.

As a new, evolving specialization, legal engineering currently lacks standardized skills and qualifications. Yet, to keep pace with tech developments, the legal industry needs legal engineers — professionals who can bridge the gap between law and technology with both technical and legal skills and insights.

Before diving into the role of legal engineers, let’s look at how technology is transforming the legal industry.

Key concepts

GenAI (Generative AI): A type of AI that can create new content, such as conversations, stories, images, videos, and music. Large language models (LLMs) are a form of GenAI. [1]

Legal (Services) Market: The entire ecosystem involved in the provision of legal services. The market was valued at around USD 980 billion in 2023. [2]

Legal Services: Work provided by lawyers, such as drafting documents, reviewing contracts, negotiating business deals, and representing clients in court. [3]

Legal Tech (Technology): Devices and tools used to interact with or assist in the practice of law, along with the skills required to use them. [4]

Legal Tech Market: The market for legal tech products and services, valued at USD 30 billion in 2023. [5]

Legal (Knowledge) Engineer: A professional who organizes and represents legal knowledge in computer systems (as defined by Richard Susskind) [6], or someone who combines technology with law. [7]

LLM (Large Language Model): A type of AI algorithm that uses deep learning and massive data sets to understand, summarize, generate, and predict new content. [8]

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation): A process that enhances the output of large language models by referencing an external knowledge base before generating a response. [9]

AI Technologies in Legal Market

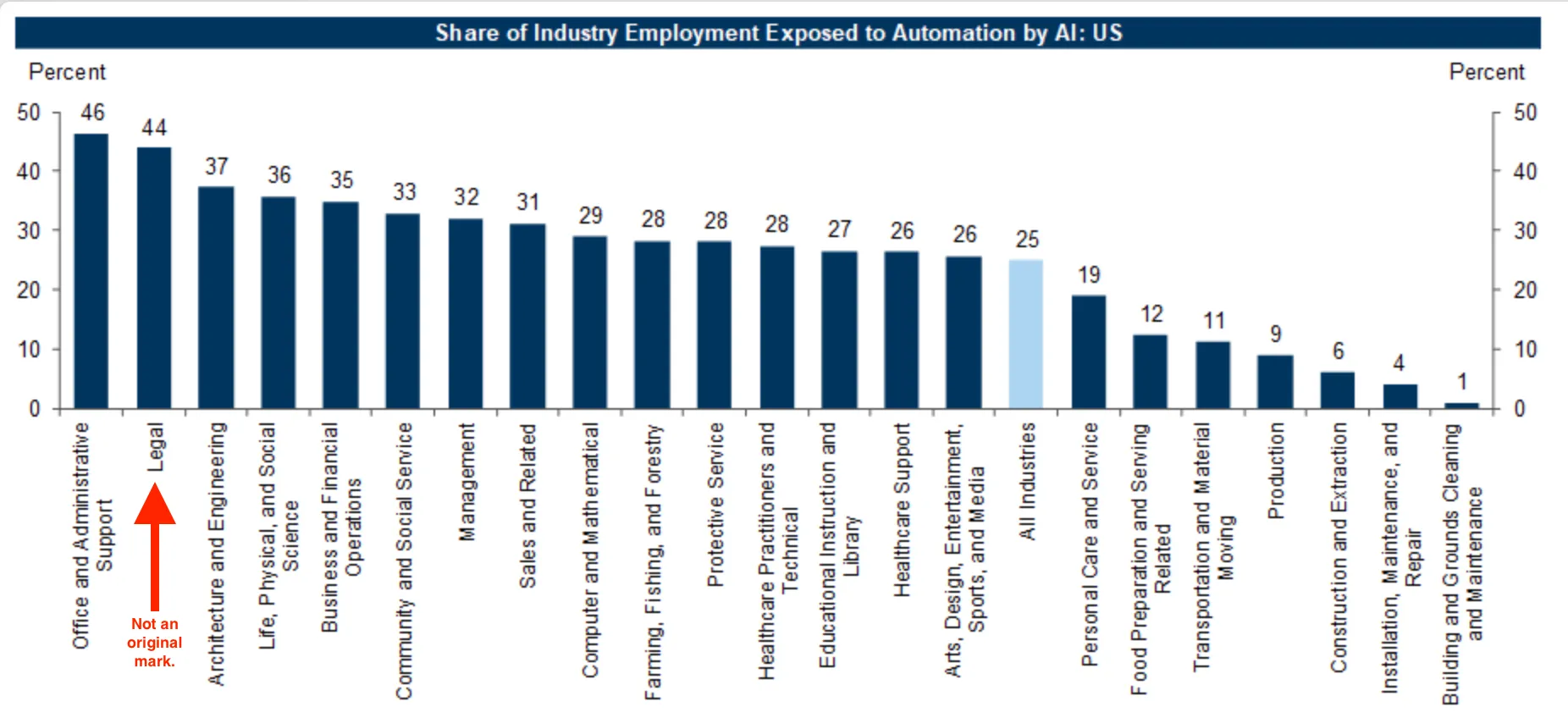

The legal market is evolving, with a strong focus on improving efficiency and effectiveness in delivering legal services. Experts agree that AI is a key driver of this transformation, to streamline service delivery, reduce costs, and improve client outcomes. [10] As a result, AI has become a powerful force behind the industry’s progress. A 2023 Goldman Sachs report ranks the legal industry as the second-most exposed to AI-driven automation. [11]

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Lawyers are increasingly recognizing the benefits of AI: 87% report that technology has improved their daily tasks, and 73% plan to adopt GenAI within the next year. Furthermore, 91% believe that access to the latest tools is crucial for maintaining productivity and adaptability. [12] The American Bar Association (ABA) has also acknowledged the growing importance of technological competence in legal services, highlighting this shift as inevitable. [13]

AI Application to Legal Services

To understand how technology is reshaping legal services, it is important to examine core legal tasks and their relationship with AI. The table below outlines key legal tasks, their exposure to AI, and specific examples of AI applications. The level of AI impact — high, medium, or low — reflects how AI can boost efficiency and simplify the work involved, not necessarily full automation.

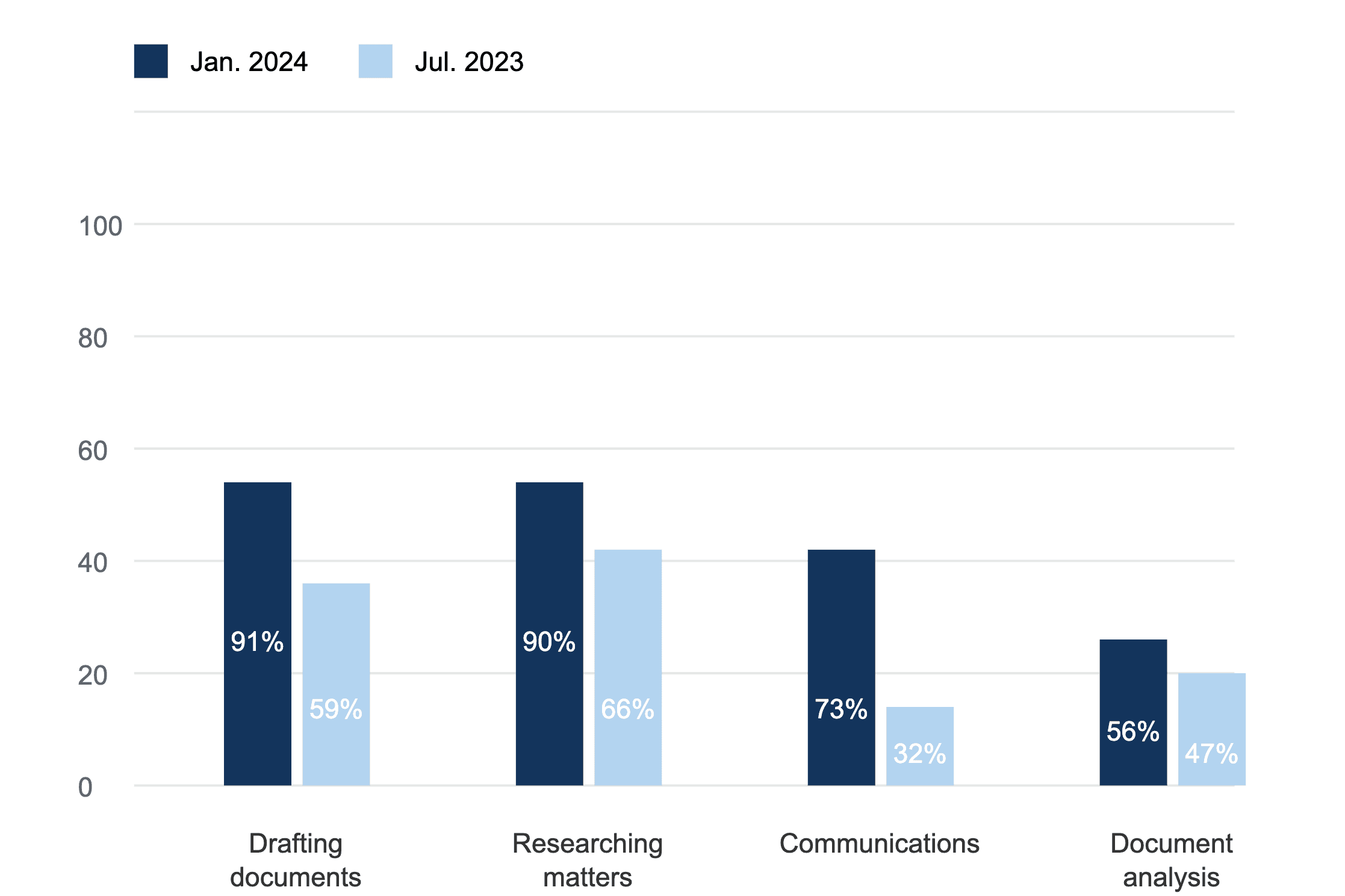

Most legal tasks are increasingly influenced by AI. In a UK survey, 90% of lawyers believed AI could significantly enhance tasks like legal drafting and research, while 73% saw its potential for improving communication. [14] Even moderately exposed tasks, such as administrative work, are expected to become more AI-driven as IoT adoption grows.

However, tasks like oral advocacy and negotiation, which have low AI exposure, face not only technical limitations but also ethical concerns. The NYSBA Task Force on Artificial Intelligence warns that over-applying AI in these tasks could risk creating unauthorized practices of law. [15]

The LexisNexis survey shows a significant increase in the adoption of AI tools: 91% of respondents prioritized drafting legal documents, up from 59% in July 2023, and 90% focused on legal research, up from 66%. Additionally, 73% cited GenAI for drafting communications as a priority, up from 33%. [16]

Additionally, an analysis of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct suggests that refusing to use technology that enhances the accuracy and efficiency of legal work could be seen as failing to provide competent legal representation to clients. [17] This highlights the growing expectation for lawyers to adopt technology to maintain professional standards.

However, in practice, the situation is not as positive as the above statistics suggest, with 69% of legal practices not currently using AI. [18]

AI Adoption Challenges in Legal Services

At first glance, the statistics showing that most legal practices aren’t using AI may seem surprising, especially since the vast majority of lawyers believe AI is useful and plan to integrate it into their daily routines. However, there are objective reasons for this. According to the ABA TechReport [19] and LexisNexis [20] survey, the three main reasons are:

Accuracy concerns, or “hallucinations”

Security and data privacy concerns

Lack of trust and reliability

Concerns such as social and ethical issues caused by biases, loss of human-centric focus and control, economic impact, and disruption[14], as well as challenges like implementation costs, learning time, and process changes, are viewed as less significant. In fact, fewer than 30% of respondents consider these issues to be major obstacles [21].

1. Hallucinations

Hallucinations occur when an LLM generates inaccurate or nonsensical output. Hallucination rates can vary across different models and depending on the domain of the question. The way prompts are crafted also plays a role in causing hallucinations.

No matter how advanced GenAI is, the risk of hallucinations exists in almost all models. In law, even a small risk of hallucination can be significant, affecting both the quality of services and the trust lawyers have in AI tools. Therefore, addressing hallucinations is crucial at present.

2. Security and Data Privacy

Security and data privacy are often cited as barriers to AI adoption in legal services, but these concerns aren’t unique to GenAI. Many APIs that provide access to LLMs strictly comply with data security and privacy regulations and do not use user data for training.

While some may overemphasize security and privacy issues with AI, it is worth noting that lawyers already handle sensitive data using other cloud-based tools. Despite this, security and privacy concerns remain a common reason for hesitation in adopting AI tools.

Security and privacy risks have always existed for digital data in cyberspace. The key question is whether GenAI introduces new risks. While using more legal data in GenAI tools may increase the chance of breaches, the nature of the risk remains the same — it is a risk associated with storing data in the cloud. Thus, standard security and data privacy measures should be effective.

3. Lack of Trust and Reliability

The third major challenge to AI adoption in legal services not only arises from hallucinations and security and data privacy concerns but also stems from several other factors, such as:

A strong dependence on prompt engineering for GenAI tools used in legal tasks;

The complexity of legal work, which often requires nuanced judgment that AI may struggle to replicate;

A generally conservative and tech-resistant attitude among many lawyers;

Insufficient training and understanding of AI among legal professionals, limiting effective use of these tools;

Concerns about job displacement or diminishing the value of human expertise in a field focused on personal judgment.

While concerns about trust and reliability may be resolved over time, some of these issues could be addressed now.

Need for Legal Engineers

Legal engineering is an emerging field, but what exactly is a legal engineer? Current definitions vary significantly — organizations promoting legal engineering offer broad explanations, while the job market demands more specific skills. In the following section, I will briefly review the current definitions of legal engineer and propose our preferable one. It’s important to note that fully defining and explaining the specialization of legal engineering requires deeper research and multiple articles.

The Ambiguity of Legal Engineering

The broad definition of a legal engineer is that they are a multidisciplinary specialist, combining both legal and technical expertise. However, the specifics of this combination are still unclear:

Does it require hands-on technical skills like software engineering, or just a basic understanding of software development?

Does it demand in-depth legal knowledge and the ability to translate legal processes for tech teams?

Should a legal engineer also be knowledgeable about AI technologies, and if so, to what extent?

These questions, and many more, remain open for discussion.

Existing definitions broadly emphasize the combination of law and technology without providing clear answers. For example, Richard Susskind defines a legal engineer as someone who organizes and represents legal knowledge in computer systems [6]. Juro describes a legal engineer as “someone that supports legal teams with the design, troubleshooting, and implementation of technology as it relates to legal processes” [22]. However, these descriptions are vague, especially in specifying the extent of technical engagement and the exact skills required.

The American Society of Legal Engineers has identified several specializations within legal engineering, some more technically focused, others emphasizing proficiency in using existing technologies [23]. However, this approach adds to the confusion, introducing multiple specializations in a field that is not yet clearly defined, making the role of legal engineers even more uncertain.

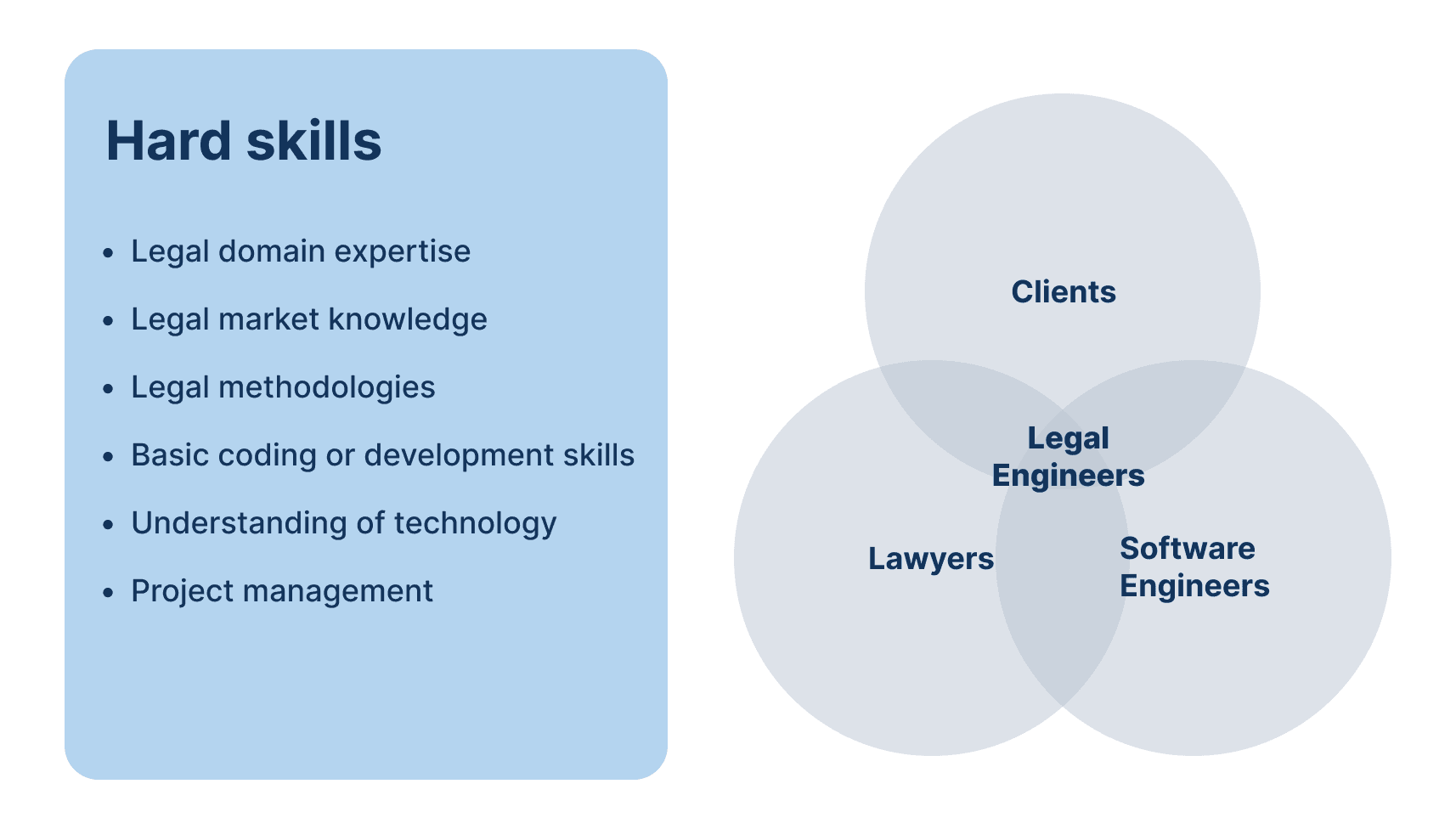

One of the most insightful articles on legal engineering is Bryter’s “What is a Legal Engineer?”. It defines a legal engineer as someone who “builds and optimizes legal solutions, products, services, and processes” [24]. While helpful, I disagree with some aspects of the skillset outlined in the article and the Venn diagram it provides. The definition still lacks clarity regarding the specific technical and legal expertise needed, leaving room for refinement.

Source: BRYTER, “What is a Legal Engineer?”

The hard skills mentioned in Bryter’s article suggest that a legal engineer is essentially a tech-savvy lawyer with basic technical knowledge. However, I believe this is insufficient to define legal engineering, as I will explain in the next section. The Venn diagram portrays a legal engineer more as a technical business analyst within the legal tech industry, acting as an intermediary between development teams and stakeholders, understanding legal processes, and delivering value to clients (end-users) [25].

The market has standard skillsets for roles like technical business analyst or product manager, but not for legal engineers. Analyzing the skills and qualifications currently demanded for “legal engineer” is a topic for another article, but it’s worth noting that requirements vary across job postings. Some companies seek lawyers who are tech or AI enthusiasts, while others require Python knowledge without specifying the exact tech stack. However, the common requirement is always domain expertise — legal knowledge.

Redefining Legal Engineering

It’s understandable that current market demands shape these views. However, if most definitions and job descriptions for legal engineers require only minimal hands-on technical skills, why label a lawyer with abstract or theoretical technological knowledge as a “legal engineer”? The emphasis here is on the word “engineer,” which typically refers to someone who “designs or builds” [26] something. This raises the question: is the term “legal engineer” appropriate for roles resembling those of a technical business analyst or product manager in the legal tech industry? It may seem that “legal engineer” is simply a convenient term for legal tech companies seeking a worker with legal knowledge who is tech-savvy or an enthusiast. But is this approach beneficial for the development of legal engineering?

Development of Legal Engineering

Will legal engineering survive as a distinct specialization without standard, unified skill and qualification requirements? I don’t think so, as specialization implies having specific skills and competencies. Most authors emphasize that specialization involves focusing on a particular set of skills, which is crucial for increasing both efficiency and quality of work in a given domain [27]. Furthermore, specialization aims to achieve specific goals by focusing resources and skills on well-defined objectives [28]. Therefore, the absence of a unified skill set will hinder the development of the field. As a reminder, our focus in this article is on the development of the legal industry, particularly legal tech.

Not only does academia suggest that a well-developed specialization is essential for efficiency in achieving the objectives of a specific domain, but it is also practically necessary for the legal market to improve efficiency, address adoption challenges, develop legal tech, and advance academic research in law. Key areas of impact include:

Making the application of modern technologies to legal services more efficient.

Overcoming AI adoption challenges in legal services, such as hallucinations, security and data privacy, and lack of trust and reliability.

Innovating faster in the legal market by providing lawyers with efficient legal tech solutions and educating them on the application of modern technologies.

Developing a new academic specialization focused on the application of modern technologies in law.

For skills, it is obvious that technical skills are crucial for creating the above-noted impact. As Colin Levy notes, that the legal professionals shall emphasize the legal literacy as AI continues to evolve.

Objective of Legal Engineering

The exploration of legal engineering as a specialization in law will be the subject of a series of articles I plan to write. However, the core objective of this specialization is straightforward:

optimizing legal work through the application of modern technology.

The term “optimize” refers not only to automating legal work but also to making it more time- and cost-efficient while ensuring it effectively serves its purpose for the benefit of society.

I intentionally use the broad term “legal work” to show that legal engineering is not limited to the provision of legal services — it also encompasses legal work in educational institutions (such as legal education or academic research) and other fields related to legal practice (such as procurement, anti-money laundering, or data protection).

Finally, “modern technology” does not mean that legacy tech is irrelevant. Instead, it implies that this specialization should be progressive enough to keep pace with technological advancements.

Conclusion

While the full definition of legal engineering and its necessary skills hasn’t been established yet, these will be the focus of my upcoming articles. Developing legal engineering into a fully realized profession is essential for the future of law.

By establishing legal engineering as a distinct specialization, the legal industry gains dedicated experts who can align legal practices with technological advancements — not only in the provision of legal services but also in the academic evolution of law. This innovative approach will benefit legal professionals and society.

References

[1] https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/generative-ai

[3] https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/legal_services

[4] https://academic.oup.com/ijlit/article/30/1/47/6563857?login=true

[5] https://www.statista.com/topics/9197/legal-tech/#topicOverview

[6] Susskind, Richard. Tomorrow’s Lawyers. 2013, page 122.

[7] https://americanlegalengineers.org

[8] https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/large-language-model-LLM

[9] https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/retrieval-augmented-generation

[10] Susskind, Richard. Tomorrow’s Lawyers: An Introduction to Your Future. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Katz, Daniel Martin. “The MIT School of Law? A Perspective on Legal Education in the 21st Century.” University of Illinois Law Review, vol. 2014, no. 5, 2014. Available at University of Illinois Law Review.

Henderson, William D. “Innovation Diffusion in the Legal Industry.” Dickinson Law Review, 2018. Available at Indiana University Maurer School of Law Repository.

Cohen, Mark A. “Law Is Lagging Digital Transformation — Why It Matters.” Courtroom Mail, 2018. Available at Courtroom Mail.

[11] Briggs, Joseph, and Devesh Kodnani. “The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth.” Goldman Sachs Global Economics Analyst, 26 March 2023. Available at https://www.gspublishing.com/content/research/en/reports/2023/03/27/d64e052b-0f6e-45d7-967b-d7be35fabd16.html.

[12] Wolters Kluwer. “2023 Future Ready Lawyer Survey Report.” Wolters Kluwer, 2023.

[13] American Bar Association. “Formal Opinion 512.” ABA, 2023. Available at https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/professional_responsibility/ethics-opinions/aba-formal-opinion-512.pdf.

[14] https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/news/quarter-of-lawyers-regularly-use-generative-ai/5118683.article

[15] New York State Bar Association Task Force on Artificial Intelligence. “2024 Report and Recommendations of the Task Force on Artificial Intelligence.” NYSBA, 2024. Available at https://nysba.org/app/uploads/2022/03/2024-April-Report-and-Recommendations-of-the-Task-Force-on-Artificial-Intelligence.pdf.

[16] LexisNexis. “Lawyers Cross into the New Era of Generative AI.” LexisNexis, 2024. Available at https://www.lexisnexis.co.uk/insights/lawyers-cross-into-the-new-era-of-generative-ai/index.html.

[17] Yamane, Nicole. “Artificial Intelligence in the Legal Field and the Indispensable Human Element Legal Ethics Demands.” Georgetown Univ. Law Center, 2020. Available at https://www.law.georgetown.edu/legal-ethics-journal/wpcontent/uploads/sites/24/2020/09/GT-GJLE200038.pdf.

[18] Miki, Sharon. Lawyer Statistics for Success in 2024. Clio, 2024. Available at https://www.clio.com/blog/lawyer-statistics.

[19] The main concerns raised related to AI included the accuracy of the technology (57.7%), its reliability (48.1%), and data privacy and security (46.5%). American Bar Association. “2023 Artificial Intelligence (AI) TechReport.” ABA Law Practice Division, 2023. Available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_practice/resources/tech-report/2023/2023-artificial-intelligence-ai-techreport.

[20] The biggest hurdles to AI adoption are concerns over ‘hallucinations’ (cited by 57% of respondents), security (55%), and a lack of trust in the current free-to-use technology (55%). LexisNexis. “Lawyers Cross into the New Era of Generative AI.” LexisNexis, 2024. Available at https://www.lexisnexis.co.uk/insights/lawyers-cross-into-the-new-era-of-generative-ai/index.html.

[21] American Bar Association. “2023 Artificial Intelligence (AI) TechReport.” ABA Law Practice Division, 2023. Available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_practice/resources/tech-report/2023/2023-artificial-intelligence-ai-techreport.

[22] https://juro.com/learn/legal-engineer

[23] https://americanlegalengineers.org

[24] Link, Jake. “What is a Legal Engineer?” BRYTER, 2023. Available at https://bryter.com/blog/legal-engineer/#h-what-is-a-legal-engineer.

[25] https://uk.indeed.com/career-advice/finding-a-job/what-does-technical-business-analyst-do

[26] https://www.britannica.com/dictionary/engineer

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/engineer

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/engineer

[27] Daniel Pink, Lynda Gratton, Howard Gardner, Michael J. Piore and Charles F. Sabel, and others.

[28] Peter Cappelli, Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad, David Ulrich, Robert M. Grant.